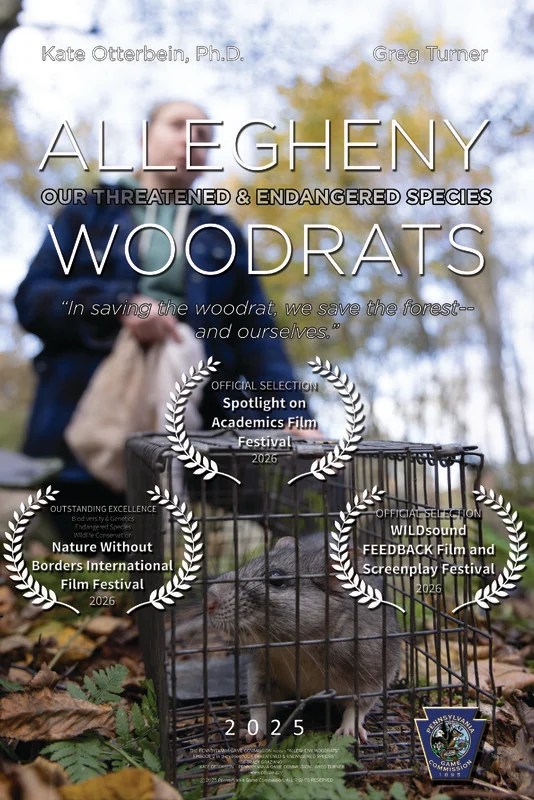

Our Threatened & Endangered Species: Allegheny Woodrat follows the Pennsylvania Game Commission and partners as they fight to save one of the state’s most elusive mammals. Once common across the Appalachian Mountains, the Allegheny woodrat has declined for decades due to habitat loss, disease, and the disappearance of its ancient ally—the American chestnut tree.

1. What motivated you to make this film?

Allegheny Woodrats is Episode II in a series on Threatened & Endangered Species. These films aim to educate folks on the challenges surrounding species conservation, and what people can do to get involved and actions they can take at home to help all wildlife. Wildlife conservation and management is complex, involving hard work, creativity, tenacity and human politics. If we tell the story well, we can ensure all of our native species persist into the future—because people will not protect what they don’t understand and they certainly won’t protect what they don’t know.

The efforts surrounding saving the Allegheny woodrat are complex and involve partnerships across state lines, with varying agencies, non-profits, institutions and universities. There are over 15 groups involved in seeing that this species persists into the future. But the challenges the species’ face is multi-faceted: from the effective extinction of the American chestnut, to habitat fragmentation that cascades into genetic isolation, inbreeding and population loss, and finally the increasing raccoon population as a result of habitat fragmentation. To save a species, we must address all of the challenges. The effort, creative thinking and dedication to our wildlife fills me with hope. Despite all the things going wrong with conservation on a bigger scale, these stories are so impactful and clearly state that we can and will affect change if we just act even in small ways.

I am driven to make a difference with the films I produce. Documentary film is a powerful tool that helps change hearts and minds—even for species or issues for which are foreign to many people. This species is a particular challenge because of the stigma in its name: it isn’t ‘just a rat’ and I hope this piece sheds some light on the importance of all wildlife, despite the name we have assigned them.

2. From the idea to the finished product, how long did it take for you to make this film?

I started documenting field work with woodrats—actually translocations—in August of 2020. So, shooting took place over five years with the bulk of it taking place in 2024. I began editing full time in late summer 2024, and tried to do re-shoots and all the interviews in early 2025. Altogether the editing process took 18 solid months.

I am one person and do all of the things: from research to writing, shooting and editing, it’s a monumental task of dedication.

3. How would you describe your film in two words!?

Woodrat quest.

4. What was the biggest obstacle you faced in completing this film?

The biggest obstacle in completing the film took place during each phase of production: the landscape itself is challenging to haul film equipment into. Bouldering and cameras don’t mix very well. Luckily, our biologists typically have an entourage of folks who eagerly tag along to help with trapping efforts—who doesn’t want to see a threatened species? I was so grateful to have lots of helping hands—but usually this just means taking in *all* of the equipment I could ever need in a day rather than being selective and leaving pieces behind. I am a one-woman band otherwise: shooting with multiple cameras, as well as taking still photographs all at the same time.

Pre-production and post-production are often smashed together with these projects because we simply aren’t given enough time to write a full-blown script in advance. I request scientific papers and pertinent background literature from the biologist and create a ‘wish list’ from that—much of which is unlikely to capture. So much of what I shoot is literally trying to document what is in front of me in every way that I can imagine in order to gather enough coverage for the editing process. And as with all documentary, there are whole events that take place that are not part of any plan and I’m just along for the ride scrambling to understand what I am witnessing and to record it all. It’s very exciting yet scary at the same time. It’s a lot of pressure to shoot in such a way as to tell a story, bring the audience along on the adventure, and also have the viewer become invested in the subject to the level where they actually care about the species in the end.

5. There are 5 stages of the filmmaking process: Development. Pre-Production. Production. Post-Production. Distribution. What is your favorite stage of the filmmaking process?

I love shooting. One of my undergrad degrees is cinematography—I just love it. My younger self wanted to only shoot and be in the field 100% of the time. However, if all you do is shoot, the footage sits there and accomplishes nothing. I’ve really started to appreciate the post-production process more and more the further I’ve gotten into my career. When I was younger, I would dread sitting in the editing bay and it would take a force of nature to be disciplined enough to sit day after day. But I enjoy organizing the mountain of footage that results from all the time in the field, and coming up with creative ways to fill the holes in the story as well as imagining the best ways to communicate the science in each of these projects. On more than one occasion, epiphanies happen in the editing room—the juxtaposition of certain shots or events spark creative ways of problem solving and of having new eyes on the subject. I’m always learning and this film was no exception; I just generally love learning natural history information, science, and then everything that surrounds the tech in the documentary film industry.

Getting footage of a nocturnal threatened species certainly posed its own challenges, and there are behaviors I felt were critical to getting the audience to care about the species. Things like caching odd items, and pruning acorns and seeds from trees are behaviors that would be impossible to get in the wild. Having a ‘pet woodrat’ to act these things out is out of the question, so I turned to animation to illustrate these behaviors. During the literature review process, I read that the species itself has an interesting tie to our state. The very first Allegheny woodrat specimen –what’s called the holotype– was collected in a cave not far from Harrisburg. Our budget is basically my pay, so fancy historical reenactments are just out of the question—but animation brought that moment to life and helps define the species for the viewer. From there it was a natural extension to also animate a couple of key behaviors for the sake of the story and so that the audience can empathize with the subject.

6. When did you realize that you wanted to make films?

I was a little late to the party with filmmaking. As an undergrad, I started out as a painting major. I had a very strong background in art as a young person, but once I got to university I was bored, frustrated, and concerned about even being able to make a living off of my art. So, I switched to biology—one of my other life passions. I found it extremely challenging, but began to miss the outlet that only art could provide. So, I muddled around a bit and started taking some photography courses. I vividly remember doing critique in photo class and the professor asking me in front of everyone if I had ever considered filmmaking—because my series of photos up on the board always seemed to tell a story. That’s what finally made it click for me: I could put my passion for wildlife and ecology together with telling stories on film. So, there I was, a senior in undergrad, declaring a dual major in biology and cinematography. From there, I entered my undergrad film in the International Wildlife Film Festival in Missoula, Montana. I was invited to take a one-week course on Wildlife Filmmaking with Jeffery Boswall from the BBC, and during that week I learned about a graduate program in development at Montana State University. A year later, I was part of the very first class in Science & Natural History Filmmaking. It was a dream.

In looking back as a kid, I grew up in a place that was developed into housing over the course of my youth. The forests and fields that were my playground were completely paved over by the time I was in high school. This really affected me deeply and I suppose played a big part in what would eventually become my career.

7. What film have you seen the most times in your life?

Probably Watership Down. I watched that over and over again as a kid. Every time we went to the grocery store I would look to see if the VHS tape was on the shelf and available for rental. If it was there, we would take it home. I would watch it, rewind it, and watch it again. It probably wasn’t healthy. Haha.

8. In a perfect world: Who would you like to work with/collaborate with on a film?

I would love to collaborate with National Geographic, the BBC, or PBS Nature or Nova on some science wildlife documentary films. I know that my science literacy and filmmaking skill set combine to tell unique stories. I do hope that even this film could be considered for broadcast. More people need to see the hard working folks behind species conservation, the passion they exude, and the persistence that it takes to save our native wildlife.

9. You submitted to the festival via FilmFreeway. How has your experiences been working on the festival platform site?

The submission process is simple and straightforward. Having everything organized and easily searchable is a huge benefit for my limited time in promoting my work. Also, the standard project page to fill out is immensely helpful and ensures that festivals get what they need to understand the film, and to hopefully promote it.

10. What is your favorite meal?

Breakfast. If I eat nothing else in a day it has to be breakfast.

11. What is next for you? A new film?

The next episode in the series “Our Threatened & Endangered Species” is on the return of the piping plover as a nesting species in the state of Pennsylvania. After more than 50 years of absence, this iconic shorebird has returned to the only suitable habitat in the state and successfully nested. This series is designed to have educational curricula to go with them to schools, universities, and sister agencies. Those accompanying materials are being written now by our very talented and dedicated staff. I am so grateful for the life that these films will have in shaping change.

All social media handles:

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/pennsylvania-game-commission

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/pagamecomm/#

X: https://x.com/pagamecomm

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/PennsylvaniaGameCommission

Website: www.pgc.pa.gov<http://www.pgc.pa.gov/>

Link to species page: https://www.pa.gov/agencies/pgc/wildlife/discover-pa-wildlife/allegheny-woodrat